Hello World, I’m Jekyll

navigateleft August 18, 2011 navigateright

Continuing the Jekyll series, today, we build our first Jekyll website. So, where to start?—install the dependencies!

Installation

There’s a more extensive list of installation instructions on Jekyll’s wiki for those with a hipster OS, but I’ll get the majority of you started, assuming you already have RubyGems installed. Simply install the Jekyll gem via Terminal and it’ll grab all the other gems that Jekyll requires by default.

$ gem install jekyll

First run

Create a new directory and cd to it. Create a file, index.html, and insert the following code:

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello world!</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello world!</h1>

<p>This is my first Jekyll website.</p>

</body>

</html>

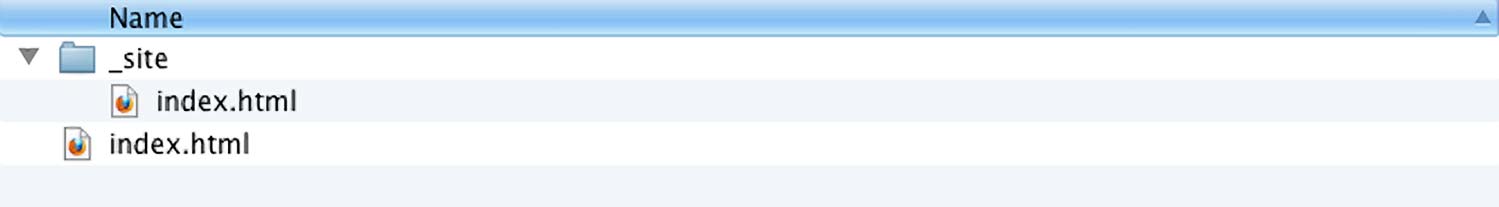

If you run jekyll now, Terminal should spit out a warning about a missing _config.yml file—ignore this for now. Terminal should also indicate a successful build of the site, creating a _site directory with your index.html in it. And just like that, you compiled a Jekyll site in the simplest form.

Testing locally

As-is, you should be able to open the index file in your browser of choice and see the result. However, as you dive deeper, you’ll want view it as one would see it on the web. Jekyll gives you the option to run a server on localhost, providing a real-life testing environment. Simply add --server $port to the end of your jekyll command, replacing $port with the port of your choice. I use 1337 for the obvious reason—I’m a baller.

Note - Jekyll’s server disregards .htaccess files, so if you rely on one, I’d suggest using an app like MAMP. It’s free and doesn’t require you to keep a Terminal tab open.

Along with --server, you can add --auto to make Jekyll watch your source folder for changes. If it detects any movement, it’ll recompile. I don’t use auto-mode as much as I should because it only indicates when a file has changed, not when the recompile has completed. For larger sites, I prefer to know exactly when the new content is visible.

Configuration

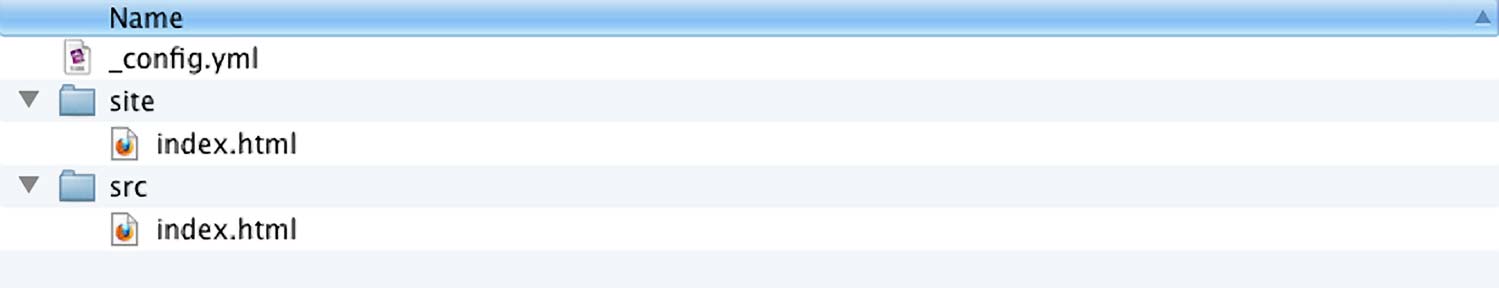

By default, Jekyll uses the source files from the top-level directory and outputs the generated files to that _site folder. I’m not a fan of this, so I use a different file tree that I specify in the configuration. I suggest you do the same by creating a _config.yml file in the top-level directory and adding the following code:

source: ./src

destination: ./site

Now your source files live in the src folder and your generated files live in the site folder. Move your index.html file to the source directory, run jekyll, and the file should now appear in site.

There are a ton of parameters you can set in the config file, but I’ll only touch on these for now. If you’re curious like me and want to jump ahead, check out the list of options on the wiki.

Note - Jekyll disregards any directory or file prefixed with an underscore, which is why it doesn’t copy the _config.yml file into _site. Keep this in mind going forward.

Layouts

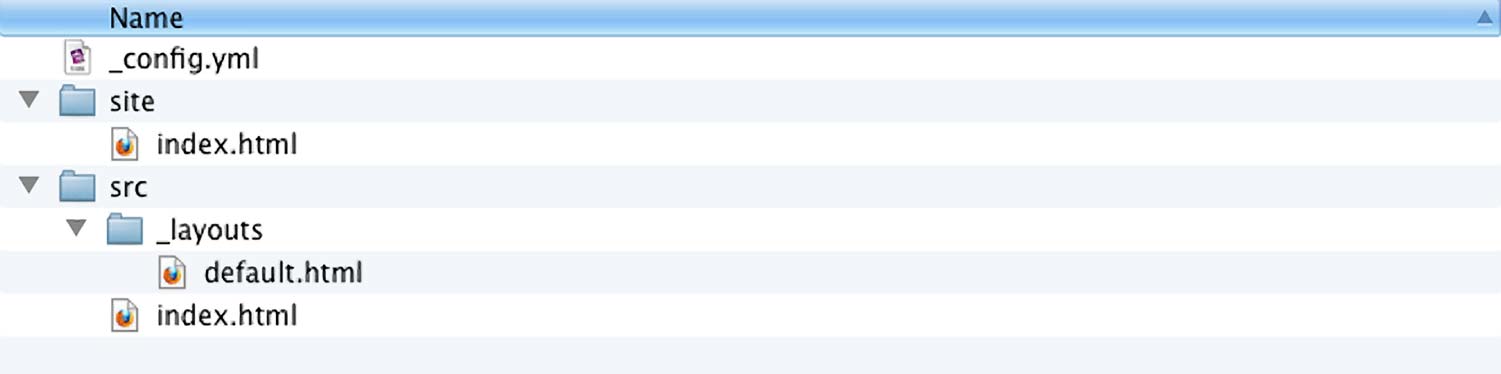

Layouts are one of Jekyll’s high points, especially when nested. Start by creating a _layouts directory inside of the source folder. Make a default.html file, which will (obviously) be the default layout used by your pages.

Copy the contents of your index page to this file, but replace the title and body, like so:

<html>

<head>

<title>{{ page.title }}</title>

</head>

<body>

{{ content }}

</body>

</html>

Jekyll utilizes Shopify’s Liquid framework for variables and processes within a page. I’ll be sure to write a post dedicated to Liquid, but for now, you might want to familiarize yourself with it.

Every layout must contain a content tag, telling Jekyll where to place a page’s content. As mentioned in the intro, you can nest layouts, where a layout’s code will replace its layout’s content tag. It might sound a bit confusing right now, but once you use it first hand, you might find yourself tap-dancing with joy.

The above code also inserts the page’s title inside the <title> tag. Jekyll provides a slew of variables, detailed on their template data wiki page. Pretty much any metadata you specify in a page’s metadata can be accessed with the page variable.

Pages

After adding your first layout, return to your index file and replace it with the following code:

—

layout: default

title: Hello World!

—

<h1>Hello world!</h1>

<p>This is my first Jekyll website.</p>

There are two parts to a page—the metadata and the content. Jekyll uses YAML to set variables for each page. It’s like XML, but without the opening/closing tags. Also, it’s very strict when it comes to whitespace, so take a moment to read up on it if you’re unfamiliar.

The metadata lives between two sets of three dashes, as seen above. Those dashes indicate that Jekyll should process this page. Before, when we had plain HTML files, Jekyll only copied the file without processing it because it lacked the dashes. In theory, you could have a page beginning with two lines of dashes, the content, and nothing else. Even so, you should, at the very least, specify a layout and title.

The content then lives below the metadata. For pages, the content must be HTML. It could be other formats, like HAML or Markdown, as long as you include the appropriate converter, which I’ll touch on in a future post.

Run jekyll one last time and it should generate the same content we had when using the plain HTML file.

Wrapping up

I’m going to stop myself here before I go beyond a simple ‘hello world’ example. If you have any questions, be my guest and ask away in the comments. In the series’ next post, I’ll help you build your first Jekyll blog, utilizing ‘posts’ instead of ‘pages’ and Liquid loops. Until then, experiment!